It has been a while since I’ve written.

Not because nothing has happened. Quite the opposite. Life has been arriving in waves, and I have been standing in the surf without quite knowing how to describe the undertow.

Winter has hit harder this year.

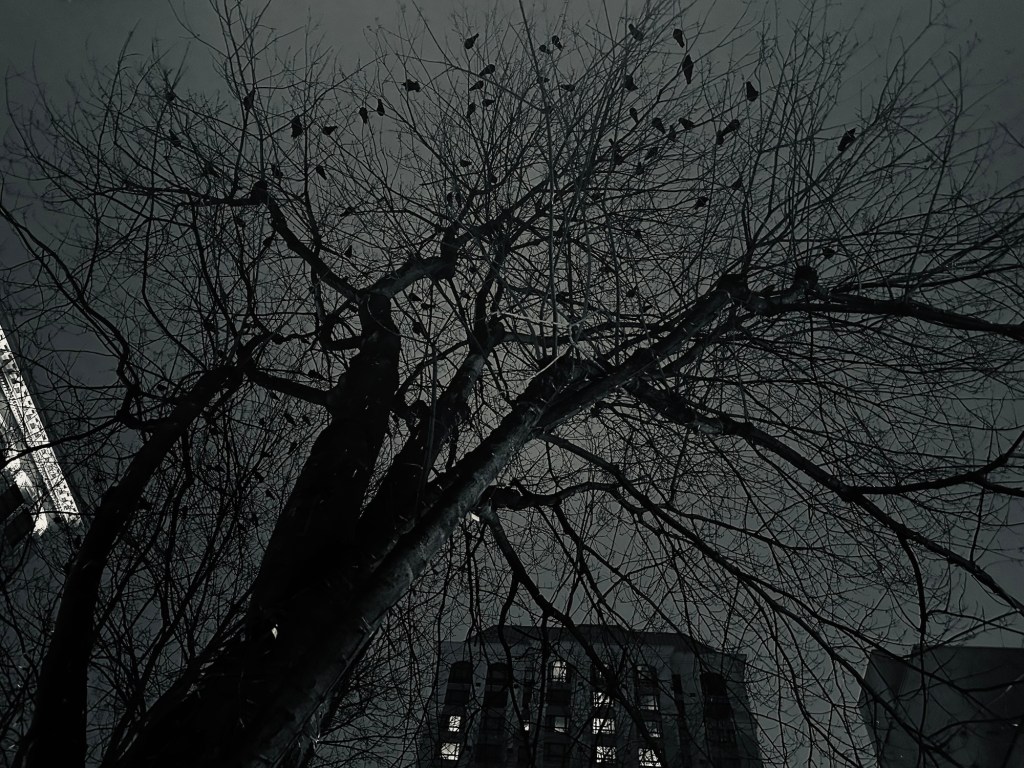

In the early morning hours, walking home from the train station, I navigate mobs of crows clustered in the trees overhead. They cry out before they let loose, peppering the sidewalk with their droppings — a crude warning system. I walk carefully. There is something about the darkness at that hour, the industrial quiet broken only by wings and wind, that feels both ancient and immediate.

Along the way I pass people sleeping in doorways. Sometimes there are dogs curled beside them, wrapped in blankets, loyal in ways the rest of us struggle to be. The city breathes differently at that hour. Stripped down. No pretense. Just bodies trying to endure until daylight.

“You’re a very empathetic person,” my therapist friend once told me. “You give so much. Most people aren’t like that.”

I didn’t know what to say then. Empathy feels less like virtue and more like exposure. You feel everything. You absorb it. And lately, there has been a lot to absorb.

The people I looked up to most of my life are dying now. My father included. I have tried to memorialize them the best way I know how — in words — but grief does not move in tidy lines. It comes in waves. Regret rides in with it. Regrets, I’ve had a few. Some small. Some seismic.

The transit agency job keeps my writing afloat. I’m taking a college course in electricity, too. Dad would have liked that. There is something solid about learning how currents move, how power is transferred. It makes the invisible visible.

When I was disqualified from the rail operator position, the union stepped in and saved my job. That was the good news. The bad news was the overnight shift — outside, in winter — moving, coupling, and decoupling trains for the next day’s service.

The yard is all steel and breath and repetition. My fifty-year-old body has begun to protest. I sleep more. I battle colds and congestion. I’ve run out of sick time. With budget cuts looming, I pray for health the way some people pray for miracles. Just get me to spring. Let me sign up for a day shift. Let light return in some practical way.

David remains my rock. At his age, working forty hours a week in retail is no small thing. I wish he didn’t have to, but it keeps him moving. That’s the trick, isn’t it? Motion as survival. My step count has never been higher since taking the yard hostler role. A coworker told me, “I have no desire to be caged in that cab for ten hours a day.” I understood what he meant. Movement feels like proof of life.

Still, I miss the sun. I miss Florida’s warmth, even though there have been days colder there than here in the Pacific Northwest. It isn’t just temperature — it’s the rain. The gray. The way it seeps into the psyche. After eight years, I sometimes think I have battled depression to a draw. Not defeated it. Not surrendered. A stalemate.

I try not to get pulled into politics. I am a public servant. But the news some days is unbearable. The cruelty. The speed with which outrage ignites. Digital life has given us constant connection and constant combustion. It is hard not to look. Harder to look away.

I think often of the summers when I worked in the parks. The disconnection. The way nature set the pace. I fell in love in Yellowstone. It was, without exaggeration, the best summer of my life.

There are alternate versions of me that sometimes feel more vivid than the one I inhabit. The version who eloped to Italy with Ann. She loved me. It was true. I often wonder what that life would have been.

But there was a secret then. A stigmata I carried too long. It shaped my choices, narrowed my courage. Decades pass in the space of one unresolved truth. And just like that, the realization lands: I will never be a father. The sting comes sharp and sudden, like a Georgia yellowjacket on a hot afternoon. You don’t see it coming. You just feel the burn.

At my annual physical, I learned I have high blood pressure. Dad had it too. I ask myself why I cannot relax. Am I still trying to prove something? Am I restless because some part of me believes another life-altering opportunity has slipped by? Is this as good as it gets?

I flew to Alabama to see my mother and brother. I won’t write more about that. Empathy again — the instinct to protect, to soften edges, even when they cut me.

Tomorrow night, I will return to the train yard. The crows will still be there. The cold. The coupling and uncoupling of cars. The small prayers whispered into the fog.

My spirit is not broken. But it is bruised.

And I am hopeful — stubbornly, irrationally hopeful — that this static feeling will pass, that something in me is still recalibrating, that winter, like grief, like regret, like love withheld and love remembered, is not the whole story.

It is only a season.

See What Readers Have to Say